NSLIG July 2019

Back to Meeting Notes 2019

Notes from the July 2019 Meeting

[hr height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

The meeting started in the usual way with Nick Vespo’s Linux News. Unusually, the first item was about Windows. With the 1903 update of Windows 10 users can run “sand-boxed” applications. To run an application in that way, first check that the machine supports HyperV via coreinfo. If HyperV is supported, select it and Sandbox.

Run the program in the sandbox, and when it is finished, the program and its components will be removed from memory without any leftovers. When operating, the program will not affect any other program(s) running at the same time.

A video was then shown of a demonstration of Scalpel – a data duplication program. The demonstration used the dd command inside Scalpel to copy the contents of a device to the root directory after checking the dd command to ensure correct operation.

The Open Forum session was quiet at first, then David Hatton spoke of his efforts to update an early model Raspberry Pi B. It was slow at first and got slower, probably due to all the new Raspberry Pi 4 owners updating their new toys from the same repository location. Even though the Raspberry Pi B was made in 2012, the latest updates were installed and ran well, if a little slower than on more recent Raspberry Pis. A good example of backwards compatibility.

Netflix found a security problem with Linux. It has since been fixed. We have no details of what the problem was and what was done to fix it. Hmm!

Linux and Windows have different approaches to the basis for time on the machine. One version uses local time zone as a reference – the other uses UTC. This can make it difficult when sharing files between the two OS’es, because – for example – it might be possible to try to access a file that has not yet been created according to the time on the partner system.

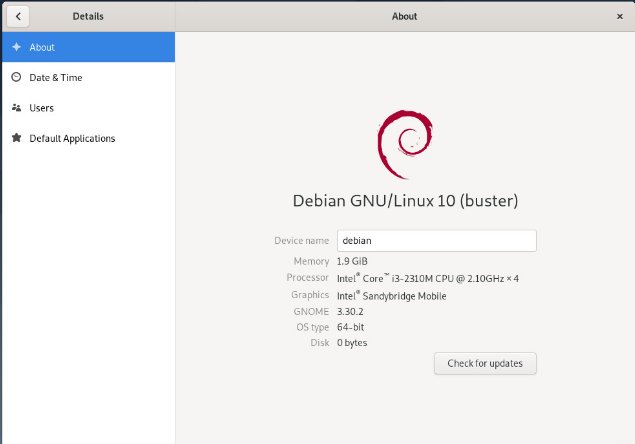

After the social break, David Hatton presented a first look at the latest updates to two distributions – Debian 10 (known as “buster”) and Mageia 7. Mageia has echoes of Mandrake/Mandriva. Both Debian and Mageia use Wayland as the default compositor for the Gnome desktop rather than Xorg, although you can use Xorg if Wayland has problems with your hardware.

Debian uses Gnome as a standard desktop, but also supports the use of a number of other desktop environments, including KDE, XFCE, Cinnamon and MATE. It comes with over 50,000 packages in total, so it is not surprising that a number of desktops are included/supported.

Both distributions support a root account separate from the user account and include the configuration function called “tweaks” (included in a vast package list) that allows a user to make changes to the Gnome user interface such as font and title bar changes. The MATE interface is described as “more Windows-like” in screen layout than the default Gnome interface.

The following screenshots show Debian displaying the basic details of the system it is running on and some of the installed applications.

Debian 10 displays the basic system details.

The Gnome desktop on Debian 10 showing some installed applications.

The Mageia distribution started as a fork from Mandriva and is a community project. Like Mandriva it is based in France. There are several flavours of ISO available, including: Plasma, Gnome and XFCE, and a “classical” ISO if you want to install multiple desktops such as Cinnamon or MATE. David showed the Gnome desktop for demonstration purposes.

Mageia 7 Gnome desktop showing some applications

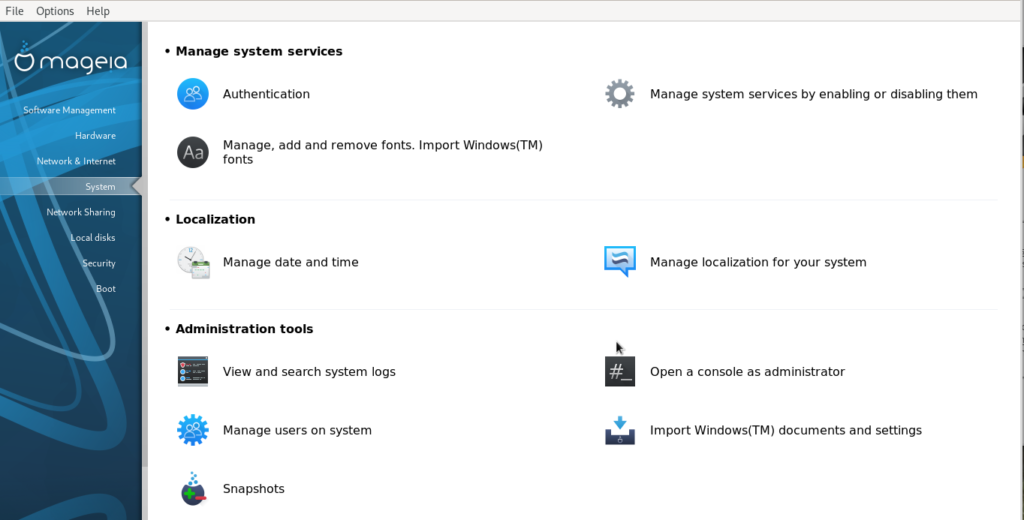

Mageia has its own package manager called “dnf”, (which does not stand for “did not finish”) which supports the .rpm package format, but it also uses urpm for package management. A significant feature is the Mageia Control Center, a system configuration and administration utility allowing users to manage their systems simply and effectively through a suite of interrelated GUI programs accessible from a centralized interface.

Mageia Control Centre showing system options.

In general, the Mageia distribution has the feel of a complete operating system, rather than one that integrates various pieces from different sources.