NSLIG – January 2019

Back to Meeting Notes 2019

Notes from the January 2019 Meeting

[hr height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Our first meeting of 2019 was opened with Linux News that gave us the illusion of time travel, because it was all about the initial competition for the IBM Personal Computer in 1983. The video was from 8-bit Guy, who has a lively and informative style.

The two competitors who were first out of the box were Compaq and Hyperion, and they built IBM-compatible computers without infringing patents or copyright because the IBM machines used all commercially-available components. The only proprietary item was the BIOS, and that problem could be circumvented by developing an equivalent.

Compaq was founded by three former Texas Instruments employees; there was no comment about who founded Hyperion. There was some commentary about the external cases of the two machine types, in particular comparing the “portable” versions to the IBM version. Apparently, Hyperion had some problems with reliability of their machines and with product support; problems that were not experienced by Compaq.

One of the areas that was seriously competitive was the screen display, with the MDA and CGA technologies each having advantages and disadvantages. Compaq produced a “portable” computer that was about 25% cheaper than the IBM portable, and it stockpiled those machines against the possibility that IBM would have supply problems. When the supply problems did happen, Compaq was able to sell off its stock-pile and went on to be a very successful personal computer supplier.

The Open Forum session started with a comment that use of the Internet was not very widespread in Australia when it first became available. An example was given of Telstra Research, which in 1991-92 had some 700 employees and a comprehensive internal ethernet network, but it only had a single 9.6Kb connection to the Internet shared by all employees.

Concerns were expressed about the failure of Apple devices (iPhones etc.) because of cracked screens, and the Apple policy of not fully supporting devices that had been repaired outside the Apple eco-system. A U.S. court struck down the Apple attempt to prevent user repairs, but subtler tactics were used after that decision.

There was a short discussion about the ability to scan documents on a Wi-fi-connected printer. In many cases, the printer sets up its own Wi-fi Access Point, and there should not be a problem in communication.

And so …. To the first Social Break of the meeting year.

And then …. to the first main presentation of the meeting year too.

The presenter was David Hatton and the topic was “An Introduction to Linux Flatpaks”.

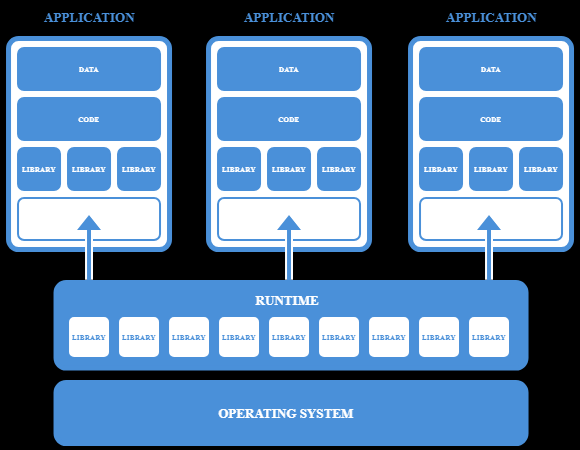

The Linux Flatpak does not need Allen keys or construction diagrams, but does require the application developer and the user to follow a process. It is a framework for distributing applications on Linux. It is open source and the work is done by an independent group, with the program originating from the X development group (XDG) and promoted by Red Hat/Fedora. The technical requirements are that applications should meet some of the freedesktop standards.

Flatpak applications can be installed on 18 major distributions currently. They come in two parts: the application, with any exclusive libraries; and the runtime components, that can be shared with other applications. The apps. can be installed for only one user (e.g. for testing), or for all users (perhaps for production).

The apps. are “sand-boxed”, running independently of other apps and not aware of them. In that respect they have some similarities to containers and the Snaps available with Ubuntu. The runtimes and apps. do not depend on distribution versions.

A flatpak installed as a single user version will put the flatpak files in the users’ home directory at ~./local/share/flatpack , a multiuser version has flatpak files installed in /var/lib/flatpack . A flatpack and runtimes are identified by a three-part name in the format Com.Author.Appname. For example: LibreOffice has the flatpack name: org.LibreOffice.LibreOffice.

The flatpak website at http://docs.flatpak.org/en/latest/ has some well written documentation, including the diagram shown below …

Flatpak application environment

The advantages claimed for Flatpaks include:

-

One app can be distributed it to the entire Linux desktop market.

-

Applications are developed and tested in an environment that’s identical to the one users have.

-

Flatpak’s build tools are simple and easy to use and come with a full set of documentation.

-

The app can be available to a rapidly growing audience of Flatpak users, with Flathub.

-

Runtimes provide platforms of common libraries that can be depended on.

-

Flatpak makes it easy to bundle unique libraries as part of the app.

-

Flatpak apps continue to be compatible with new versions of Linux distributions.

-

Flatpak is developed by an independent community, with no lock-in to a single vendor.

At the end of the presentation there were comments that the Linux community should be co-operating to build a single platform to handle flatpack-style applications, rather than allowing competitive platforms to operate in the market. But that is a subject for the future, and time travel is not with us …. Yet!