Book Review

12th July 2020

Tim McQueen

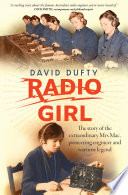

Radio Girl

David Dufty

Allen & Unwin

302 Pages

There is a great deal of similarity between the early days of radio here in Australia and the beginnings of home computing. The Metropolitan Radio Club (Sydney) was one of the biggest amateur hobby clubs in New South Wales in the 1920s. There were specialist shops where one could purchase every requirement from components to complete radio sets. One of these was The Wireless Shop, taken over by Miss F V Wallace in 1921. Florence Violet (known as Violet) was born in Melbourne in 1890. The family moved to the quiet mining village of Austinmer (NSW) where Violet was fascinated by the trains and signals on the Sydney/Wollongong line. In her schooldays she made up electric circuits with bells and installed lights in dark cupboards because of her mother’s poor eyesight. In 1904 she won a scholarship to Sydney Girls High School, completed her senior year in 1909 and determined to become a Mathematics teacher. One Sunday morning in 1922 Violet decided she was wasting time teaching and should go back to study Engineering. There were no female engineering students and prospective students had to be apprenticed; firms did not accept females for an apprenticeship. Eventually, she was able to take over her brother’s engineering firm and apprentice herself.

Some of Violet’s early Wireless Shop customers introduced her to Morse code and set the path for her future. She became the first woman in Australia to hold a wireless experimenters licence and was very involved in early broadcasting in Sydney. She was one of the founders of Wireless Weekly magazine, which eventually evolved into Electronics Australia and ultimately Silicon Chip.

On an overseas trip in 1924, she spoke on KGO San Francisco (a broadcast that was picked up in Sydney; listeners were astonished to hear an Aussie accent). Around this time she was dubbed ‘the radio girl’ in newspapers and magazines. She married Cecil McKenzie in 1925.

In 1930, Violet opened the Women’s Radio College, She felt women made excellent salespeople and were also better at repairing sets than men. As the use of electricity spread in the early 1930s, there was a rash of electrocutions. She set up educational programs and broadcasts on the safe use of electricity and electrical appliances. Another topic of interest was cooking with electricity.

In 1938 Violet was involved in the establishment of the Australian women’s flying club. The club organised courses for required pilot skills – one of these requirements was Morse code. With the approach of war, she started the women’s emergency signalling corps. Her students called her Mrs Mac, she called them her girls.

With the pervasive sexism of those days, she was not called on to train male recruits. However, some sixty RAAF recruits attended her sessions voluntarily. Violet wanted to get women into the Air Force; the authorities resisted. She had more success with the Navy and was one of the founders of WRANS. The WAAAF came into being as well, and even the Army accepted female signallers over the strong opposition of General Blamey. Violet and her graduates trained signallers, mainly in Morse, but also in semaphore, from all Australian services as well as United States personnel. Unfortunately, in peacetime, her contributions were rapidly forgotten, although she was awarded an OBE in 1950. She lived until 1982.

David Dufty has written a fascinating book which will appeal to most Melb PC members.

Recent Comments